Competent adversariality hides too

Yesterday, in competent evil hides, we discussed how bad actors who are openly so allow coordination against them to happen with the consequence that they’re expelled the from the communities they act in, while those who are skillful at keeping plausible deniability slip through shared epistemic cracks, and how that ends up being, effectively, a selection process for that type of competent bad actor.

Today I want to generalize that idea further: it’s not just “competent evil” that needs to hide as a condition of its success: it’s adversariality in general.

Here’s an example of what I mean:

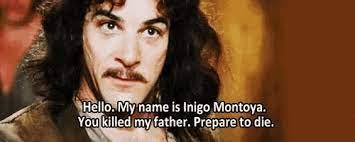

This meme makes for a good example of how adversariality works. How adversariality works in fiction, that is.

Notice all that exposition. All that legibility. That exposition is a necessity of the genre in which Inigo Montoya’s adversariality is happening: fiction is designed to be consumed in the third person and, thus, must be made clear to the reader.

But real-world adversariality is designed to not be consumed in the third person. Ideally not even in the second person. Real-world adversariality is designed to stay hidden.

Here is how a real-world adversariality expert talks about it:

“All warfare is based on deception.

Hence, when able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must seem inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.”

—Sun Tzu

Now, sure, waging warfare in 500 BC China is a very specific skill set that most of us don’t really have or need, but my claim is that this lesson generalizes. Not just beyond 500 BC China but beyond warfare into adversariality in general.

Loudly declaring your adversariality gives your enemy time to coordinate and protect and rally and sway opinion. Keeping it hidden robs them of the opportunity of doing all that. Making it that much more likely you’ll succeed.

And, thus, the same dynamic we discussed yesterday applies here: because there is a kind of adversariality (hidden) that beats out another kind (overt) then there is de facto, a selection process for that type of adversariality: adversariality that hides.

And because it hides you can’t see it just by naively looking for it. You must infer to its existence.

The power players could smell another player. But they probably could not make sense (and just dismiss) an earnest nerd who places all his cards face up on the table... but there are so many cards lol and it takes a lot of work to make it legible through the epistemology of power